When the Slavic hordes came rumbling out of their homeland to fight and settle in what we now refer to as Eastern Europe (as well as a few other European countries not so forthcoming about their Slavic heritage), Christianity was ascendent in most of the lands of the Roman Empire they overran. Christianity was more of an urban-based religion, and there were still places of older traditions which remained, certainly. And as well, it had only been a few hundred years since The Diocletian Persecutions that kicked off the fourth century proved to be the last gasp of paganism as the official state religion of the Romans. Rome had christianized its lands, but it was a lot more complicated than just declaring a nation to be Christian.

However, the remnants of Roman Christianity still abound in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Balkans. The ruins of third, fourth, and fifth century churches can still be found - in one case in Herzegovina a graveyard surrounds the ruins of a fifth century basilica, and that graveyard, still in use, has been in use since the basilica was built 1500 years ago. The Balkans offers a profoundly deep area-heritage that rivals the tours of holy places in the Middle East and Rome itself.

The invading Slavs, however, were not interested in Christianity. Nor were they interested in urban settlements or, for that matter, written education. Already quite depopulated due to successive invasions, wars, and plague - the area we know today as Eastern Europe was settled by the invaders, who brought their own paganism with them. It would take three hundred years for the process of re-converting the lands to Christianity to begin, and it would take a few hundred more years for it to bear any semblance of being completed. And, even upon completion, often the pagan beliefs remained in another form, syncretic with Christianity. Several Slavic cultures retain a practice of sitting quietly for a moment before heading out on a journey - a legacy of pagan beliefs about the spirits of the home, who need to be given time to detach themselves from the legs of Slavic travelers.

It wasn’t just the focus of the Slavic religion that was different from early Christianity, but worship itself had a completely different format - one that makes concrete and sweeping statements defining the religion of the new inhabitants of Eastern Europe more difficult. Rather than grandiose and lasting stone temples, the Slavic brand of paganism tended more toward worship in nature. And the aversion toward written learning meant that religious practices were only recorded, when they managed to be recorded, by observers (who were usually hostile).

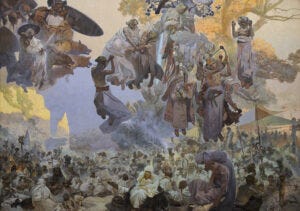

All that aside, we do have some surviving ideas and understandings about Slavic religion (which do not necessarily coincide with neo-Slavic worship).

To begin with, much like in Nordic mythology, Slavic mythology represented the world of the dead, living, and gods with a giant tree.

The Chronica Slavorum, which gives a version of Slavic history up to 1171, describes the Slavic religion as having one main god, from which everything else (including lesser deities) came and who should be worshiped universally. This supreme in certain areas was called Rod, although many sources also refer to Perun as the supreme god. Etymologically related to Slavonic words that deal with family, Rod was said to begin time inside a golden egg.

The Primary Chronicle from Kyivan Rus describes a statue of Perun, whose name continues to reverberate in Slavic areas as the god of thunder. Mountains throughout the Balkans bear variations of Perun’s name, including in Bulgaria, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. These traditional names have survived for generations. Perun was sometimes described as an eagle nested in the heights of the tree, while his counterpart in the realm of the dead, Veles, was pictured as a snake amongst the tree’s roots.

Veles, as god of the Slavic underworld, was also the god of disease. His name, too, survives topographically in several countries; most notably the city of Veles in Northern Macedonia and a mountain near Guca in Serbia. Veles is often associated with a dragon as well, which has evolved into some syncretic practices in Slavic Christianity using Saint George.

One of the deities most recognizable by name in the West is the goddess Lada, although her name is memorable because it is the eponym of the most famous Russian car - a car so important in the Russian national mythos that even Vladimir Putin owns one (although he likely prefers his more modern armored vehicles). Lada was mentioned later than many deities in the historic record, not until the 1400s. The goddess of love and fertility, her place in the pantheon has actually been a matter of some dispute, most-favored-car status notwithstanding.

Another Slavic god who has left behind topographical evidence is Triglav, the Three-Headed-God. Mount Triglav in Slovenia bears his name, although, as is the case nearly universally in the study of Slavic history, there are historians who vehemently disagree with this origin. Triglav’s name is fairly obvious. He had three heads, and his name Tri (three) glav (head) is merely a descriptive.

The Slavic world is large, and the pantheon of Slavic gods reflects that. While representations of particular deities may stretch across the Slavic world, there are also several whose existence is mainly locational. It’s an important point to make, as much of what the Western World understands about the Slavic World has been filtered through the propaganda of the Soviet Union in the twentieth century. Information on the Russian centered pantheon is available easily, finding information on the deities of the Southern Slavs much less so.